This Sorry Spacesuit 014- On Gatekeepers: In Defense of Looting

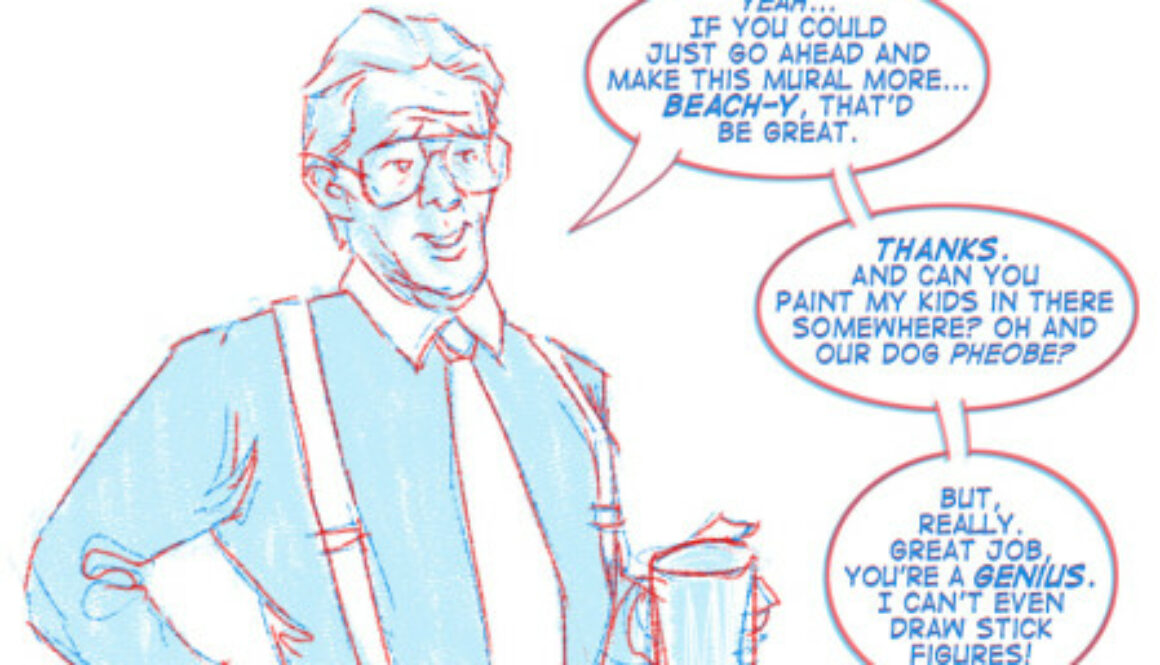

In the 15 or so years that I was a professional artist, almost every job I did had some kind of employer. Each project naturally had someone to commission it. Sometimes these people were patrons, allowing me an opportunity to excel by trusting the skills that I had developed. And sometimes they were more like that guy from Office Space:

As a professional being commissioned, I completed the task to their satisfaction. In any job there is compromise and getting paid to make art is no exception. Sometimes the compromise would make the work better and in those instances, the employer became something more valuable: a collaborator.

But there have been two instances where the employer was really a Gatekeeper: collecting and curating artists like keys on a ring, and using them to unlock a gate that was keeping them apart from a world that only they could see. A world which had no compromise.

Like our discussion in issue 5, some of the best art is achieved by the artist seeking to be a lightning rod; listening with closed eyes and doodling like some automatic-writing clairvoyant. Working to stay sharp and waiting for the hair to stand up on the back of their neck as the air electrifies with the presence of… something good. Each of these instances were significant to me because I was told by a gatekeeper that I had control, and I was given a great idea.

With the first one, I buckled to the gatekeeper’s expectation and paid the price. I learned my lesson and when the second project came around, I defended the idea and was stopped from doing the job.

Some artists don’t buy that crap about lightning rods. Some artists think everything boils down to hard work. And some artists are perfectly content to be keys, especially if it means they get to make a living holding a brush instead of a shovel.

But for me when you’ve been handed something really good coddled by the lightning, you’re doing a disservice to whatever Gods hand out ideas to compromise ANY part of it.

Here’s the story of the first one. In the interest of brevity I’ll leave the second one out. (Maybe for a future issue…)

You are here.

Nich and I (pictured above) stumbled across the idea.

I’m sure you know those boardwalk cutout displays that you put your head into; the ones that usually have the pretty lady and the strong guy hilariously painted on the front.

There’s an interesting sort of transformation that takes place when you use one. You put your face through a hole in a piece of wood and you become something else. You step sideways into another life, or another time.

For you Harry Potter fans, it’s like a pensieve. You push your face through into a different world and hold it there while a loved one stands in front of you with a camera, and you can’t help but feel funny, being the object of this incredibly simple magic trick.

And the resulting picture is proof that you lived as something that you are not for a few seconds.

These little painted machines create empathy out of thin air, really.

So we thought why not take the idea and make the scenes tragedies, instead?

Frankly the idea still scares me a bit.

I see a room filled with these things: Jackie chasing parts of JFK down the back of their car, the people pointing up at Martin Luther King Jr’s assassin, a little girl running naked down the street her back blistered from Napalm. Burning Monks, Nazi’s, Jonestown, Kent State. All these charged moments with holes where the faces should be. Time machines with empty seats, all waiting for you step in and inhabit their moment.

How do you get someone to try one? Who does it first? Do they smile nervously when they put their head in? Do they allow you to take a picture of them?

Do we judge them when they do it? Do we take note of which one they use, and attempt to draw conclusions about the size and weight of the monster that lives inside of them?

…Each time you put your head in one, does it get a little easier?

We sat on it for a while. Logistically neither of us had the time or space to make these large scale pieces, and I couldn’t take the time from paying work to make something without knowing who to sell them to. (That kind of decision is really one of the saddest things about making a living off art.)

But the idea stuck around. A few years later I was invited to be a part of a new project; a gallery was reclaiming advertising billboard material and was collecting artists to paint them. They had a sponsorship from Van Wagner to plaster LA with these giant pieces of fine art. 3 artists were attached to each full-sized billboard, giving me a 10×10′ space to do whatever I wanted. Not a paying gig of course, but what great exposure (that statement is the second saddest thing about making a living off art. And a good first whiff of a gatekeeper.)

And so, presented with the opportunity to do whatever I wanted, the idea came back; innocently whistling and running a stick back and forth across the top of my picket fence.

Hurricane Katrina had recently happened and there was a viral bit of news that went around at the time. The AP had captioned two separate photos which ran together. One of a black kid “looting” food and the other of a white couple “finding” bread. Although the story behind how this happened is more mundane and doesn’t seem to point to a conspiracy (Snopes has the story) it had scratched open something awful that most of the country felt but couldn’t get at. And the idea of generating empathy and meaningful conversation around that moment seemed too good to pass up. That feeling of electricity came back.

But the trick was in finding out how to represent this. I could paint the empty hole where the head should be, but I didn’t think it would translate well at a distance. So I thought I’d need to paint it as if someone was using it. But who would want to sit for that?

I finally figured, if I was going to ask people to take this as anything more than a cheap joke, I had to be the first person to try it on.

I did a sketch that was approved, and I started going to the gallery every day to work.

As the piece developed, the gallery owner began to take interest. So did the people who dropped in, though it seemed to me like the black people who came in didn’t care for it one bit. The mailman would come in and be nice at the door but seemed a lot cooler when I said hello. There was a guy who came every day to sweep up and do odd jobs and I’d see him occasionally leaning on his broom, sizing me and the billboard up. But I thought I was just being paranoid and overly sensitive. I’d look at the thing for hours and I thought it was working.

When I was almost done, the gallery owner started asking me questions about it. He admitted that he hadn’t realized that this was the point, even though he had approved it. He expressed concern that it would be taken the wrong way and the man who swept up the place got into the conversation.

What happened next was an exchange of ideas between two strangers regarding the murky area surrounding race, privilege, and experience. The gallery owner pretty quickly fell out of the conversation, embarrassed I think because he never looked at the sketch. But the handyman and I talked for an hour. After I explained the intention, he loved it and thought the idea could be useful. But for him and the mailman and most other people of color that came in there, the image of this kid clutching Diet Pepsi in waist deep water was too new and racially charged to be appropriated. And the bigger purpose of the piece, the empathy part, was getting lost.

He gave me two valuable insights that fueled my decision. He flatly stated that he felt Katrina, and the government’s response to it, was a black man’s holocaust. And he said that this thing, sitting above a highway couldn’t be properly processed by someone who has 4 seconds to look at 1/3rd of a billboard while going 60 miles an hour.

He said that all anyone was going to see was a white man’s head in a black man’s tragedy.

I began to feel that my choices had been wrong, I went through the options of how to get it back on track. Nothing seemed clear about it anymore and it’s a bewildering and panicky thing to have been trusted with a 10-foot blank canvas that will be seen by thousands of people and to be told once you’re done that it doesn’t work. We talked about how we could change it, and removing the race of the empathizer seemed the only option. So I painted myself out.

It looked ridiculous. I tried to salvage the blank space with a passive-aggressive “you are here.” but the point had been broken, like when you push too hard on a pencil trying to cross something out.

Then, in the vacuum left by the fleeing good idea, all the little daily stuff rushed back into my head. “You’re already over schedule, just finish the damn thing.” “Other artists need to work on their section, get out of the way” “You have real, paying work to do.” Life was now out there with a stick on the picket fence and I didn’t have the time to sit quietly, waiting for the lightning to come back and help me figure this thing out.

A few weeks later it went up at a busy intersection, but I felt like a failure.

4 or 5 months after the unveiling, the gallery owner called me and said the billboards were headed to San Francisco and he was wondering if he could get another artist to paint over my section. There were 2 other great paintings on that billboard and mine was limiting their exposure. I told him to go ahead. It’s funny how 1 square foot of bad decision can ruin 30 feet of good work, like a burn hole in a couch cushion.

I’m not really disappointed with the gallery owner, who seemed to sell me an opportunity then pull the rug out. And I’m certainly not disappointed with the man who suggested I change it. Everyone was incredibly well intentioned, and that hour-long conversation was one of the most valuable ones I’ve ever had.

But more than an admonishment, it was undeniable proof of concept for the original bolt of lightning. And that part of it I ignored. I was disappointed in myself for not following through with the idea I was given.

I was disappointed that, when it came time to put my head in the hole, I backed out.

And I learned that the next time I see a gatekeeper no matter how well intentioned, I’ll hold that idea up out of the floodwater. Maybe even put it in a plastic bag to save it from getting all wet.

I guess to me, some things are worth looting.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this essay. If you’d like to receive more stories like this, please sign up for the This Sorry Spacesuit newsletter below. Once a month or so you’ll get an email with a story or discussion on art, music, history etc.- Something like what you’ve read here. And when you sign up, you’ll get access to the archive- over 30 more posts, stories and essays like this.

This isn’t a marketing platform, just letters in a digital bottle tossed into the glimmering sea of content, that hopefully will spark conversations which are more than 140 characters long. There is NO sales-pitching or spam.

Only 16% of his dreams survived;

Only 16% of his dreams survived; In 1884, George Eastman invented and patented a camera. Plate cameras had been around for a while, but his camera made practical use of his real innovation: film. He created these things while trying to find a way for his little photography business to grow, so that he could care for his mother, who had been taking in boarders at their house to support his dreams since his father had died in 1862.

In 1884, George Eastman invented and patented a camera. Plate cameras had been around for a while, but his camera made practical use of his real innovation: film. He created these things while trying to find a way for his little photography business to grow, so that he could care for his mother, who had been taking in boarders at their house to support his dreams since his father had died in 1862.

Having no way of seeing the movies beforehand, he often used publicity stills and the boilerplate plot info that the studios would send to theatres in order to come up with his work.

Having no way of seeing the movies beforehand, he often used publicity stills and the boilerplate plot info that the studios would send to theatres in order to come up with his work. But they hardly seem like the same hand is responsible for them, as each set jumps genres and bends towards the film’s aesthetic (or plainly improves upon it)

But they hardly seem like the same hand is responsible for them, as each set jumps genres and bends towards the film’s aesthetic (or plainly improves upon it)

A few weeks after that, he was heading home when it started to rain. “On my way home I cut through the alley behind the theater and found my posters thrown out with the trash,” he said. “It was raining so they were all slopped around, and I thought, ‘Holy mackerel, why didn’t they tell me? I did all that work and they just threw them away!’ It made me sore.”

A few weeks after that, he was heading home when it started to rain. “On my way home I cut through the alley behind the theater and found my posters thrown out with the trash,” he said. “It was raining so they were all slopped around, and I thought, ‘Holy mackerel, why didn’t they tell me? I did all that work and they just threw them away!’ It made me sore.”